60 years later, Bobcats reflect on OHIO learning, living and ‘the best years of our life’

For Dr. Bernard Kokenge, PHD ’66, Ohio University isn’t just the place where he earned a doctoral degree he never intended to get. It’s the community where he and his wife started their family and continue to make memories. And it’s where some sage advice from a professor led to a career that took his work—and his name—to the moon and beyond.

“The older you get, the more you look back,” says Kokenge, who resides in Springboro, Ohio, with his wife, Joy. “We look back on our days at Ohio University and how it was so formative for us—not just the academic part but the living. It helped us to prepare for the future.”

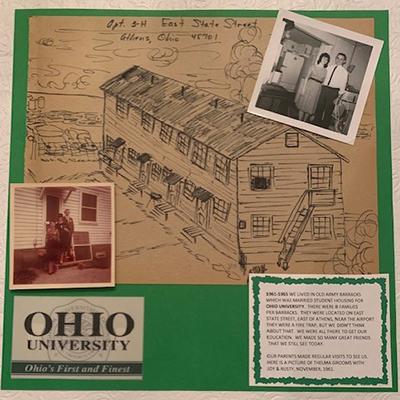

The newlywed couple arrived in Athens 60 years ago this month, with Joy expecting their first child and Kokenge accepted for graduate studies in the Department of Chemistry. They moved into old military barracks on East State Street that had been converted into married student housing—14 units total, each housing eight families, and all without air conditioning.

Kokenge came to campus with a goal of earning a master’s degree and becoming a college professor. A qualifying exam given to graduate students at the time instead landed him in the chemistry department’s doctorate program—OHIO’s first PhD program, established in 1956.

“There might have a been a little bit of disappointment in the sense that it looked like I was going to be there a little longer,” Kokenge remembers. “Joy chimed in right way, saying, ‘Let’s stick it out.’ We were there, and we wanted to make the most of it.”

Kokenge was one of approximately 15 graduate students in the program that year—all men and only two of them married. He studied under the direction of the now late Professor Emeritus of Chemistry Dr. James Tong whose research was supported by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. It was research that not only proved valuable in his future career but provided Kokenge a summer grant that supplemented the $1,800 stipend he earned during the rest of the academic year.

“We didn’t have much, and we really had to scrape by,” Kokenge says. “But it was the best years of our life.”

The Kokenges were there in 1963 when comedian Bob Hope touched down at the Ohio University Airport—then located near their military barracks apartment off East State Street—for a performance on campus. They watched as President Lyndon B. Johnson delivered his “Great Society” speech on The College Green in May 1964. And, like all Athens Campus students in those days, their OHIO years were marked by regular flooding of the Hocking River, which the Kokenges remembered turned Peden Stadium into a lake and buckled the floors of Grover Center.

Their fondest memories, however, were of OHIO’s annual Homecoming festivities—and those of 1964 in particular. That was the year that Joy, seven months pregnant with their second child, was named Mrs. Ohio University through the University’s chapter of the National Association of University Dames, an organization for the wives of married students. Joy served as president of OHIO’s affiliate of the National Association of University Dames from 1963-64.

“Homecomings were always a big thing, and we always enjoyed them,” Joy says. “We got to ride in the Homecoming Parade in 1964, so that was a real highlight. We were also invited to President Alden’s home for the National Association of University Dames’ ‘Putting Hubby Through’ program.”

Indeed, Joy did help get her husband not only through, but to Ohio University, where, Kokenge proudly says, “We pursued my PhD.”

It was Joy and a professor at the University of Dayton, where Kokenge earned his bachelor’s degree in chemistry, who convinced him to pursue graduate studies. And it was Joy who took to the typewriter, using two sheets of onionskin paper separated by carbon paper, to compile all the chemical formulas and research in her husband’s 126-page dissertation.

When it came time for Kokenge to look for jobs, the now late Professor Emeritus of Chemistry Dr. Robert Kline steered the soon-to-be OHIO graduate in a life-changing direction. With several job offers in hand, Kokenge came to Kline for his advice.

Having worked with the U.S. Department of Energy’s Los Alamos National Laboratory, Kline recommended that Kokenge accept an offer from the Monsanto Research Corp.’s Mound Laboratory in Miamisburg, Ohio, a facility operated by the Atomic Energy Commission.

“He said, ‘Bernie, I can only recommend what I know about,’” Kokenge remembers of his conversation with Kline. “He had an idea of what Mound was doing, and he said, ‘You’re going to have a unique opportunity—one that not too many people will have—if you work there.’”

Kokenge started his career as a senior research chemist at the Mound Laboratory, which at the time was engaged in the development of nuclear weapon components—as an offshoot of the Manhattan Project—and the creation of a new way of generating power. Scientists at Mound had invented what was known as radioisotopic thermoelectric generators (RTGs), a type of nuclear battery fueled by plutonium-238. Kokenge’s work at Mound focused on the RTG batteries and, most notably, improving and refining plutonium-238 fuels, a task and a challenge he successfully completed, earning him a patent on the modified fuel form in 1972.

“I was fortunate to join Mound at a time when this concept of plutonium-238 heat sources was just starting,” Kokenge says. “Dr. Kline told me I’d have a chance to do some things that are very unique, and, boy, was he right on.”

Some of the plutonium-238 RTGs produced at Mound, and later fueled by Kokenge’s improved plutonium-238, powered spacecrafts and scientific instruments of several NASA missions. RTGs used during the Apollo missions and moon landing—and still on the lunar surface—studied everything from the body’s atmosphere to its seismic activity. 1975’s Viking Mars Landers, the first missions to land on Mars, included RTGs that operated for four to six years. And Pioneer 10, NASA’s first mission to the outer planets, continued to send signals back to Earth for more than 30 years, powered by Kokenge’s plutonium-238 fuel.

Kokenge’s achievements at Mound literally launched his name into space. His signature—alongside those of NASA workers and contractors—can be found on scientific instruments on the moon and on the Galileo spacecraft, which plunged into Jupiter’s atmosphere in 2003.

“None of this would have been possible without those RTGs,” Kokenge says. “They were the sources of power, the onboard power utility if you will, for all these scientific probes. We were only one small part of an overall effort, but you feel good about contributing to what the United States has been able to do over the years in space exploration. You’ve done something that’s left a footprint on our scientific endeavors.”

Kokenge moved into management at Mound, eventually becoming associate director of the laboratory, responsible not only for the space program but also for the research, development and production of nuclear weapon components.

In 1986, Kokenge finally landed the career he had set out for when he enrolled at OHIO. He accepted a position as vice president of strategic planning and program development at Kentucky Christian College, where he was also afforded the opportunity to teach chemistry and physics. He went on to become a consultant for the U.S. Departments of Energy and Labor, using his college education and work at the Mound Laboratory to help index the chemicals and toxic materials workers had been exposed to over the years.

Kokenge retired in April 2020, and as the couple embarked on a new chapter in their lives, they couldn’t help but think back to where it all began.

“It was a sad day when we moved out of the barracks,” Joy recalls. “We had such great friends down there. … We’d do limbo in the yards and have parties in the evenings. We just had a great time, and it was like a big family—and great memories.”

Those memories have continued over the years. The Kokenges stayed in touch with some of the friends they made in Athens and with Dr. Tong, last visiting with him in October 2010 when they returned to campus for a football game. And they’ve kept up with visits to their first home as a family.

In May, they participated in the OHIO @ home series, taking a virtual tour of the new Chemistry Building on the Athens Campus. The couple returned to campus this summer to see the new 34,000-square-foot facility—the 21st-century version of the research labs and classrooms Kokenge experienced back in the 1960s when the chemistry program was housed in a building across from Bentley Hall.

“I’m personally grateful to Ohio University and its professors for the training, the encouragement and the recommendations I received over the years,” Kokenge says. “Joy and I have been blessed to be able to do a lot of things over the years, and we are so grateful to Ohio University for the experience we had. It was the best experience.”